Martin Scorsese doesn’t only make films. For the last thirty years, he has also been restoring old films through his Film Foundation.

The Criterion Channel is now streaming a selection of 27 films that Scorsese has restored. I haven’t seen all of them. Here are nine out of the 27 that I have seen and liked.

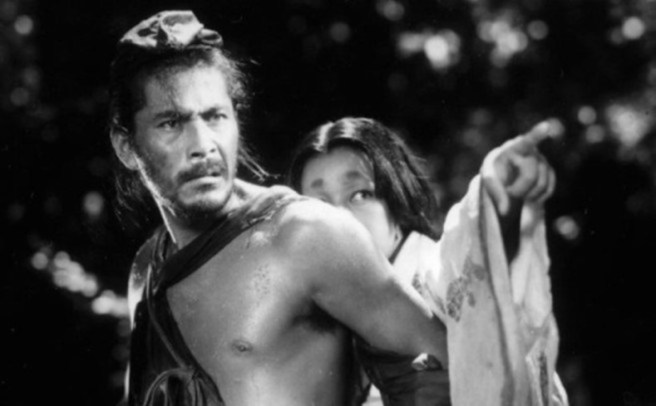

A+ Rashomon (1950)

You’ve probably seen Akira Kurosawa’s first masterpiece, but you probably remember it wrong. That’s the point – everyone remembers things differently. In medieval Japan, a notorious bandit waylays a high-born couple in the woods, ties up the husband, and rapes the wife. Or at least that’s how some of the witnesses remember it. This story is told in flashbacks, and in flashbacks within flashbacks. Kurosawa, a director known for long and expensive epics, made Rashomon as a chamber piece. The film that brought Japanese cinema to the world. Read my Blu-ray review.

A The Long Voyage Home (1940)

Like John Ford’s Stagecoach, The Long Voyage Home is an ensemble piece rather than a star vehicle. And like Ford’s earlier masterpiece, John Wayne and Thomas Mitchell carry much of the film’s story. Based on four short plays by Eugene O’Neill and adapted for the screen by Dudley Nichols (who also wrote Stagecoach). They support each other, drink, and commit minor acts of rebellion against the officers. But World War 2 changes merchant marines. Read my full article.

A- L’Atalante (1934)

It’s a common story, but done very well, thanks to director Jean Vigo’s poetic realism. A bride tries to adjust to her new family, and they must adjust to her. But it’s not a normal family. The “home” is a riverboat. The groom is the skipper, and the rest of the family are two adorable sailors. One is young, small, not too smart, and rarely talks. The other is a big lug who loves cats beyond reason. He’s also trying to fix their phonograph. Not the best honeymoon, when the groom’s co-workers are on the trip. This was Vigo’s only full-length feature; he died of tuberculosis only months after L’Atalante opened.

A- Wanda (1970)

Writer/director Barbara Loden created an extremely low-budget, independent crime thriller, and turned cheap production values into virtues. She also plays the title character, a drifter who goes where people take her. So, it’s no surprise that she falls in with a cheap crook. The movie was shot in 16mm, with bad lighting and echo-filled sound recording, and has no background music; but that lack of polish forces you to accept the people and places as they are.

A- The Red Shoes (1948)

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s extravaganza about the world of ballet dramatizes the sacrifices necessary to become a great artist. The story is sometimes weak – especially in the second half – yet there are powerful moments. The 20-minute ballet sequence at the film’s center may be the best dance sequence in a narrative film. No other film used three-strip Technicolor so perfectly.

B+ The River (1951)

This clash of civilizations appears as a friendly melting pot in this coming-of-age story set in British India. A happy English family begins to get unglued when the two oldest daughters develop competing crushes on an American veteran. There’s tragedy and near-tragedy, gentle comedy, and the warm envelope of people who love each other, even when they’re angry. Jean Renoir paints, in beautiful three-strip Technicolor, an idealized version of British India, where everyone gets along, no one rejects a mixed-race girl, and western and eastern ways of life merge happily.

B+ Blackmail (1929)

A beautiful young woman ditches her Scotland Yard detective boyfriend, flirts with an artist, then kills the artist in self-defense. The next morning she’s at the mercy of a blackmailer. Alfred Hitchcock’s second thriller already shows the touches of the master. The heroine’s night wanderings after the incident, her reaction to casual gossip about the murder, and the blackmailer’s breakfast prove that even this early Hitchcock could keep us on the edge of our seats. Blackmail was both Hitchcock’s first talkie and his last silent (there are two versions).

B+ Ugetsu (1953)

Kenji Mizoguchi shows us the cruelty of medieval Japan, only this time with ghosts. War brings profits and hope to two ambitious peasants…until the war comes to their doorsteps and scatters them and their families. If only they had listened to their level-headed wives, who told them to be happy with their lot. But for one husband, hoping to become a great potter, it becomes difficult to tell the living from the dead. There has always been something ghostly about Mizoguchi’s images; this film makes no bones about it.

B+ The Music Room (1958)

The Indian aristocracy is dying, but one high-born nobleman can’t quite see it. In Satyajit Ray’s tale of music and denial, Chhabi Biswas plays that lost aristocrat, still bringing musicians to his home to entertain himself and a dwindling selection of guests. His money is also dwindling, and his influence on others is already gone. Ray takes a mildly sympathetic and considerably critical look at this lost fool who doesn’t understand that he’s now just another man.